Click the coloured regions to learn about them.

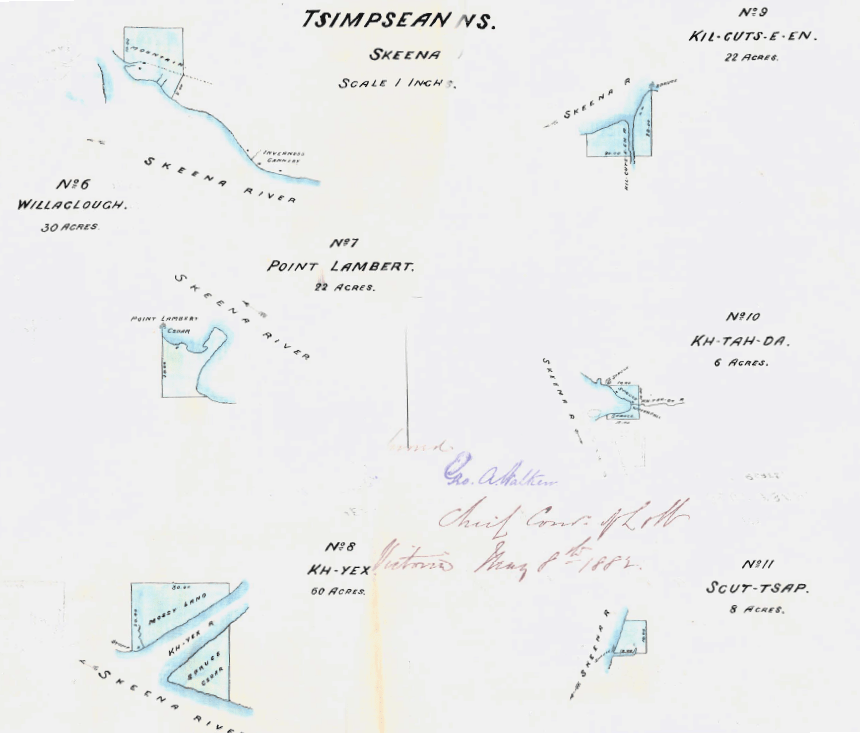

The Port Simpson Reserves, on the Lax Kw'alaams First Nation's Traditional Territory

Basic information

O’Reilly allotted 10 reserves for the Lax Kw'alaams First Nation, which were called the Port Simpson reserves. The largest, Reserve no. 2, spanned approximately 70 400 acres along the sea coast between Port Simpson and the southern end of Digby Island. He allotted one fishery in this region in Reserve no. 5 at the mouth of the Clo-ya River.

_at_Port_Simpson_1888-min.jpg)

Sidewheel steamship Princess Louise at Port Simpson, BC, August 1888. Photographed by

Richard Maynard. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/file:Princess_Louise_(sidewheeler)_at_Port_Simpson_1888-min.jpg

O'Reilly's Perspective

O’Reilly’s travels to Port Simpson were tiring, but he worked hard to get his job done. He woke up before sunrise and went to sleep well after sunset each day so that he could get as much done as possible. Sometimes when he tried to meet with someone, he could not find them, and had to proceed without their input. Many times, the weather stopped him, with strong winds and tides not allowing him to travel. When disputes between settlers and Indigenous people arose, O’Reilly tried his best to be fair. One time he received complaints from settlers and the local missionary that a reserve was taking away land from a settler’s homestead. After interviewing people on both sides of the issue, he decided that the fairest solution was to split the land evenly between the Indigenous people and the settler, rather than choosing sides.

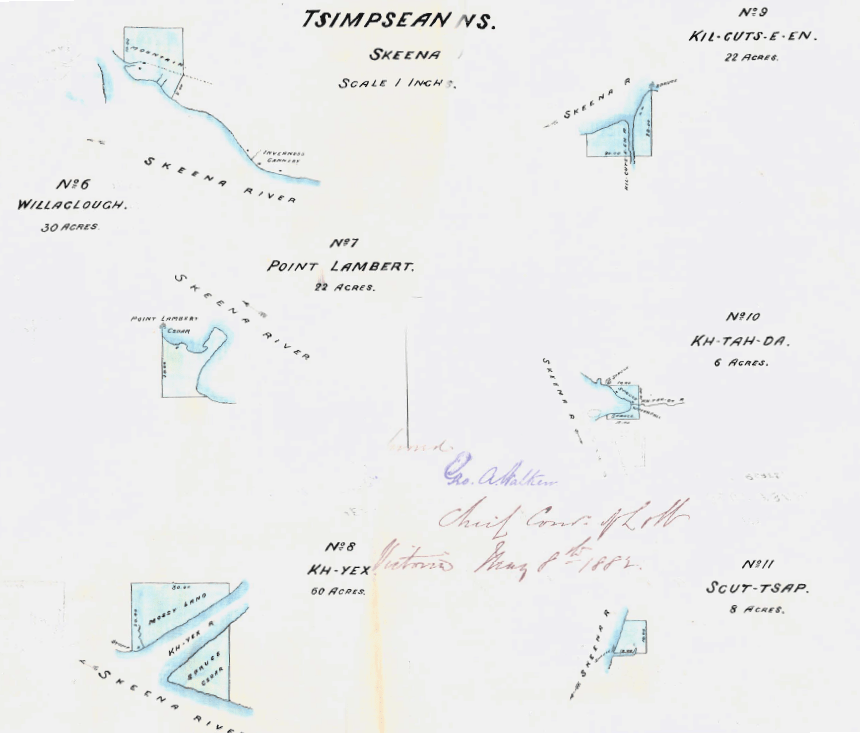

Sketches of the Port Simpson reserves in 1881, sketched by O'Reilly's surveyor, Ashworth Green. Copied from Provincial Binder 6, Federal and Provincial Collections of Minutes of Decision, Correspondence, and Sketches, collected by the Union of BC Indian Chiefs Research Department and Resource Centre. http://jirc.ubcic.bc.ca/node/11

Lax Kw'alaams Perspective

Many residents of the Port Simpson reserves were unhappy with how O’Reilly had dealt with them. In particular, they were angry that O’Reilly had excluded a significant amount of farmland from the reserves. They said that O’Reilly was in a hurry and that they did not understand what was happening. Also, O’Reilly allotted the reserves while the chiefs were not present.

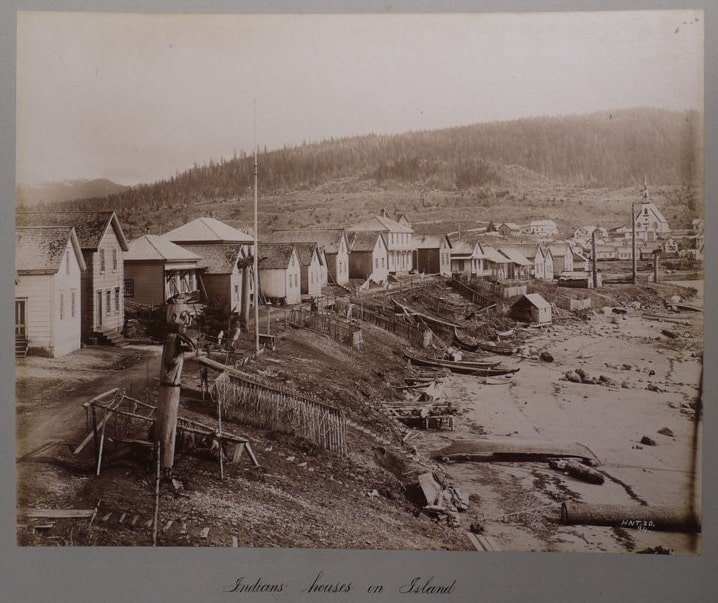

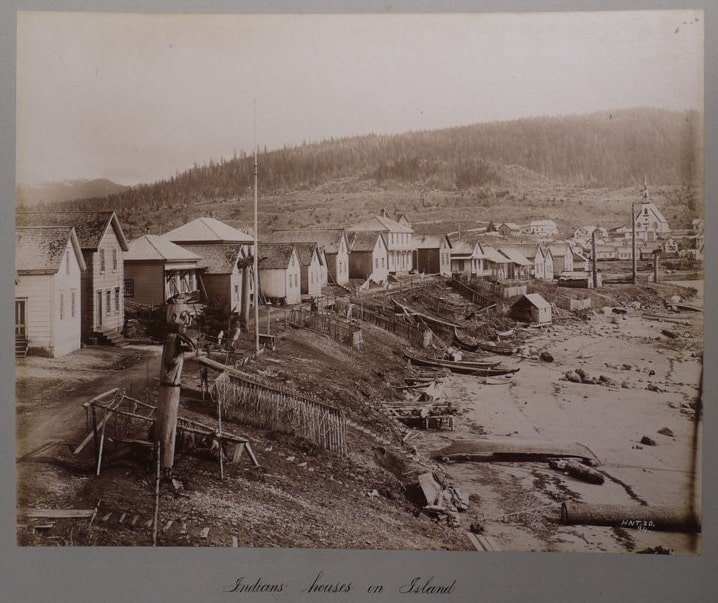

'Indian Houses in Port Simpson.' Photographed by Horatio Needham Topley. Published in Views of Alaska, 1894. http://www.wayfarersbookshop.com/Wayfarers-December2014.php

The Pemberton Reserves, on the Lil'Wat First Nation's Traditional Territory

Basic information

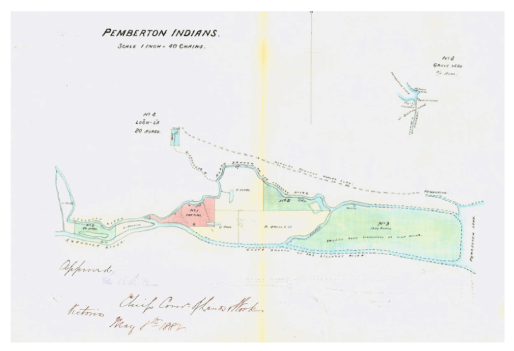

O’Reilly allotted 5 reserves for the Lil'Wat First Nation, which he called the Pemberton reserves. He allotted two fisheries, one in Reserve no. 4 on the Birkenhead River, and in Reserve no. 5 on the Lillooet River. He also allotted one graveyard in Reserve no. 5 that was just ¾ acre.

Celebration at old Mt Currie reserve. Photographed by Nancy Gilmore. Courtesy of Pemberton and District Museum and Archives. http://www.pembertonmuseum.org/collections/photos/gilmore-nancy/p1223_celebration/

O'Reilly's Perspective

The Pemberton Valley was an ideal location for settlement, so O’Reilly had a hard time finding good reserve land that had not already been claimed by settlers. When he arrived, he was surprised to find that the area had been abandoned by those early settlers. He asked the province to reclaim those properties from their abandoned owners to lay out the reserve. He saw great potential for farming there.

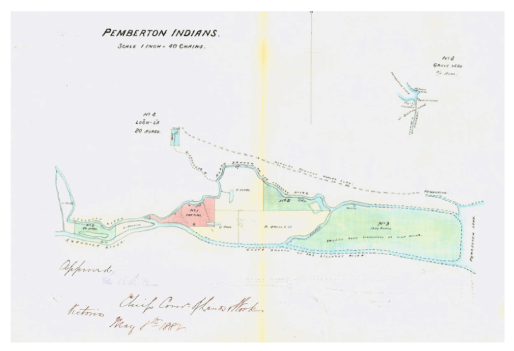

Sketches of the Pemberton reserves in 1881, sketched by O'Reilly's surveyor, Ashworth Green. Copied from Provincial Binder 6, Federal and Provincial Collections of Minutes of Decision, Correspondence, and Sketches, collected by the Union of BC Indian Chiefs Research Department and Resource Centre. http://jirc.ubcic.bc.ca/node/11

Lil'Wat Perspective

When O’Reilly arrived at Pemberton Meadows, Chief Stager (James) greeted him and was happy he was there to settle the land question early on. The previous governor, James Douglas, had promised certain land to be reserved for them in 1859 or 1860, but O’Reilly told them that he could not find any record of it in the Records Office in Victoria. O’Reilly allotted five small reserves and put in a request for the rest of the land, but after checking up on it once didn’t care to follow through. Eventually all the land was taken by settlers. Could you imagine how this made them feel?

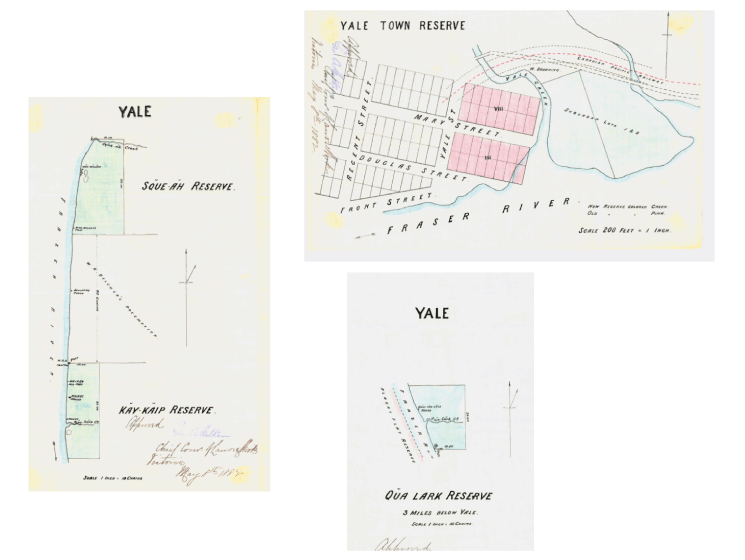

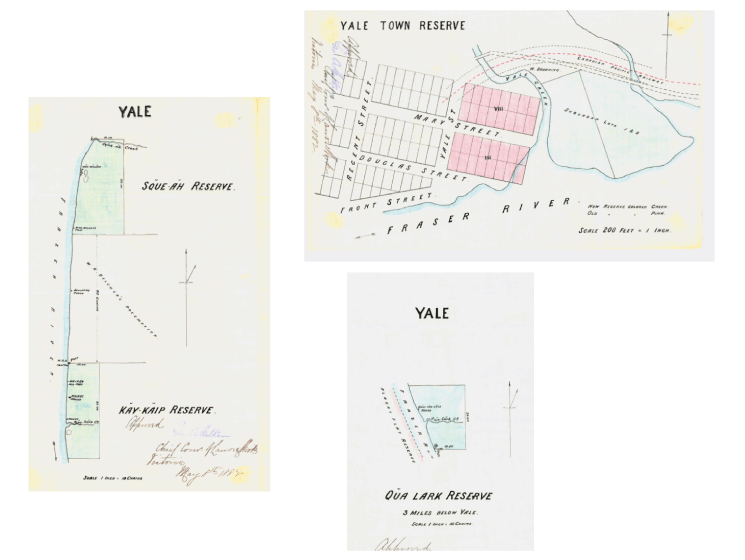

The Yale Reserves, on the Yale First Nation's Traditional Territory

Basic information

O'Reilly allotted 4 reserves for the Yale First Nation.

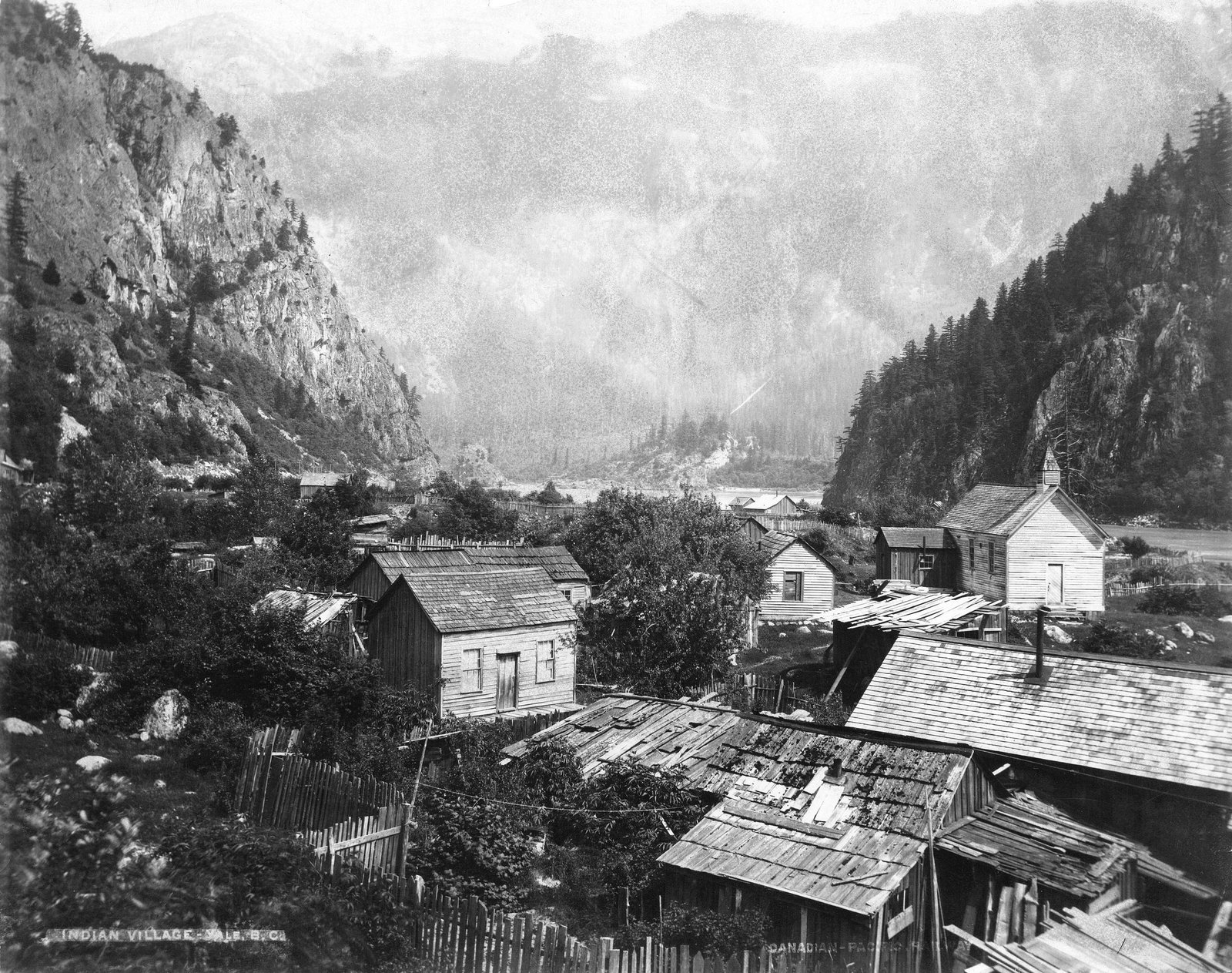

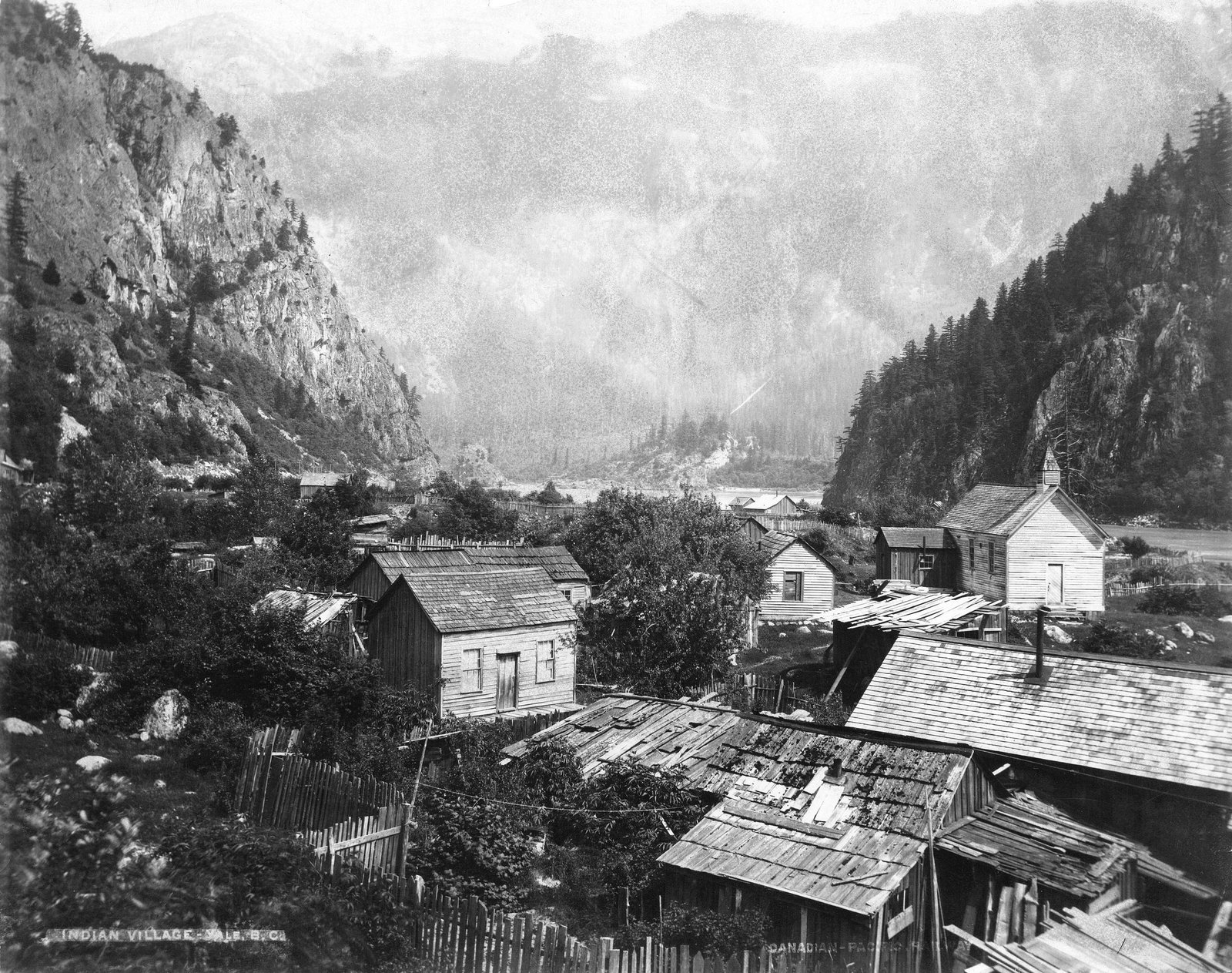

Photograph of Yale reserve, circa 1900. Taken by James Skitt Matthews. Courtesy of Vancouver Archives, AM54-S4-: Out P1060.

O'Reilly's perspective

When O’Reilly travelled to Yale, the land he found there was light and sandy and covered mostly with fir trees. He felt that once the trees were cleared, the land would be well suited for cultivation. O’Reilly also set aside some fishing stations for the reserve, but to him, agriculture was more important. This is because there was a belief at the time that fishing, hunting, and gathering were primitive actions, and that taking up agriculture was superior and civilizing.

Sketches of the Yale reserves in 1881, sketched by O'Reilly's surveyor, Ashworth Green. Copied from Provincial Binder 6, Federal and Provincial Collections of Minutes of Decision, Correspondence, and Sketches, collected by the Union of BC Indian Chiefs Research Department and Resource Centre. http://jirc.ubcic.bc.ca/node/11

Yale perspective

Sproat, the Reserve Commissioner before O’Reilly, had assigned reserves with plenty of access for fishing, as agriculture was more difficult in this area due to the poor soil. People in the Yale Band made their livelihood by selling firewood to settlers who lived in Yale. However, Sproat had not included a lot of the forest in the reserve, and they were worried that when the settlers found out, they would just go and log it themselves. The Yale Band requested for the reserve to be expanded. O’Reilly arrived there shortly after to survey the area and start the process of expanding the reserve. The additional space was finally added to the reserve in 1884, but it was a slow process.

The Alexandria Reserves, on the ?Esdilagh First Nation's Traditional Territory

Basic information

O’Reilly allotted 3 reserves for the ?Esdilagh First Nation, which he called the Alexandria reserves. He allotted fishing rights in Reserve no. 3 on the west bank of the Fraser River. He also reserved one graveyard on Reserve no. 3, situated on the Hudson’s Bay Company's land.

Photo of Alexandria Bridge along the Cariboo Trail, 1920. Wilson Postcard Collection. http://www.oldphotos.ca/archivos/record.php?collectionID=2&recordID=1734448208

O'Reilly's perspective

O’Reilly sympathized with the Alexandria Band because a lot of the land promised to them by the former reserve commissioner had been taken by white settlers. However, because he was unable to find any record of the land reserved, he could not do anything about it. He did reserve the land that they were living on, and gave them access to flowing water, but it was 4 miles away, and wouldn’t provide proper irrigation.

Sketches of the Alexandria reserves in 1881, sketched by O'Reilly's surveyor, Ashworth Green. Copied from Provincial Binder 6, Federal and Provincial Collections of Minutes of Decision, Correspondence, and Sketches, collected by the Union of BC Indian Chiefs Research Department and Resource Centre. http://jirc.ubcic.bc.ca/node/11

?Esdilagh perspective

The Alexandria Band were very frustrated by the settlers taking their land. The former reserve commissioner had laid out reserves for them, but now they were told by O’Reilly that no record could be found of it, and because of that no action could be taken against the settlers. They grew angry that the only flowing water given to them was too far away to be useful. All that was suggested was that an irrigation system might be created in the future.

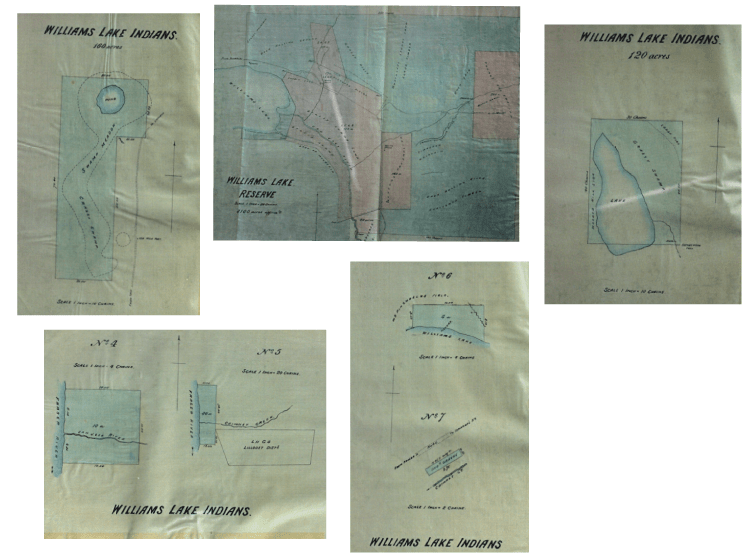

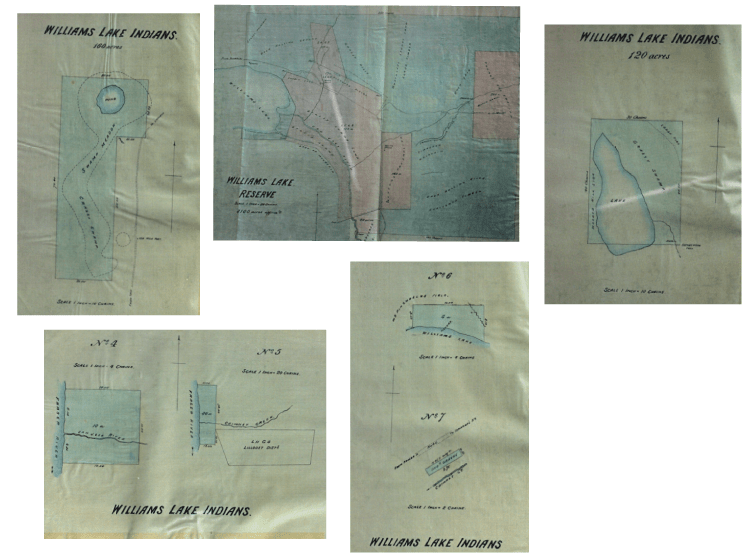

The William's Lake Reserves, on the T'exelcemc First Nation's Traditional Territory

Basic information

O’ Reilly allotted 14 reserves for the T'exelcemc First Nation, which he called the William's Lake reserves. He allotted three fisheries in Reserves no. 4, 5, and 6. He also reserved 8 separate graveyards.

Picture of Soda Creek near William's Lake, 1868. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Soda_Creek_on_Fraser-min.jpg

O'Reilly's perspective

O’Reilly and the government wanted the Williams Lake Indian Band to have enough land necessary for farming. Canada even bought an estate and several properties to be included in their reserves. Additional land on the mountains was laid out where the people of Williams Lake had harvested winter feed for their animals. One area was especially important because it had a lake from which they drew their supply of water. They stored their water on the mountainside with a series of dams.

Sketches of the William’s Lake reserves in 1881, sketched by O'Reilly's surveyor, Ashworth Green. Copied from Provincial Binder 6, Federal and Provincial Collections of Minutes of Decision, Correspondence, and Sketches, collected by the Union of BC Indian Chiefs Research Department and Resource Centre. http://jirc.ubcic.bc.ca/node/11

T'exelcemc perspective

O’Reilly did admit concern about the land reserved. Around 500 acres were worthless, as it was rough mountain top covered with trees only fit for firewood. He did not believe that the land reserved elsewhere would provide sufficient soil for farming. He also believed that the two streams on the reserves would not provide enough water for irrigation in the dry season. But, being on a tight schedule, he had to move on.

Before O’Reilly had arrived at Williams Lake, Chief William had reported that his people were facing starvation. The government tried to make more reserves, but huge delays allowed settlers to get there first. This meant that all of the good land and fishing spots were already being settled.

_at_Port_Simpson_1888-min.jpg)